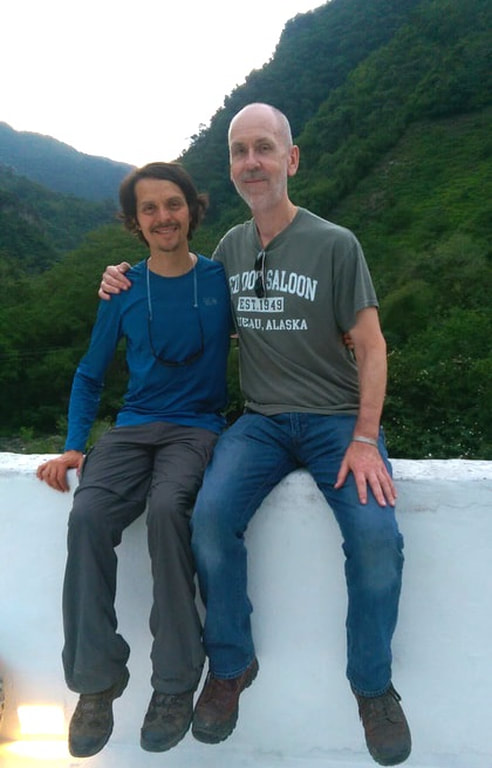

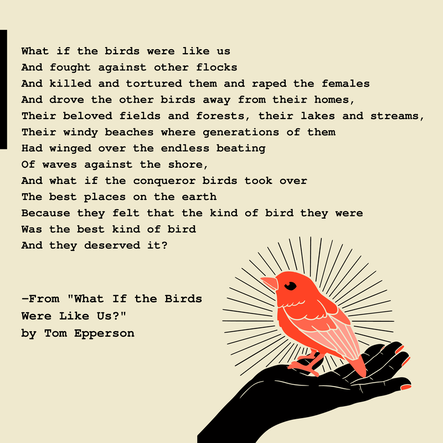

As a young man in Arkansas, I wrote hundreds of poems, but when my boyhood friend Billy Bob Thornton and I headed for California to chase our Hollywood dreams, I mostly left poetry behind. But recently a funny thing happened. I unexpectedly found myself writing a poem for the first time in 32 years. It was a spooky supernatural tale called “The Hotel by the Sea.” I loved writing it; it was like half a lifetime hadn’t happened and I was just a poet with a pencil and paper again. I didn’t know if I’d ever write another one, but well, guess what, the muse has struck again! I was standing at a window of our house in Culver City and watching the squirrels in the front yard when I got the idea. I’ve been feeding walnuts to the squirrels since my wife and I moved here 23 years ago and love to watch them as they browse for food and chase each other around in the trees. As I stood there, sipping my coffee, they seemed so beautiful and peaceful and innocent, so different from how human beings behave with their anger and violence and wars (look at what’s happening now in Ukraine!). I thought, what if squirrels behaved like us?, and instantly I knew I had a poem. Except “What If the Squirrels Were Like Us?” didn’t have quite the right sound to it. So I present to you “What If the Birds Were Like Us?" What if the birds were like us

And fought against other flocks And killed and tortured them and raped the females And drove the other birds away from their homes, Their beloved fields and forests, their lakes and streams, Their windy beaches where generations of them Had winged over the endless beating Of waves against the shore, And what if the conqueror birds took over The best places on the earth Because they felt that the kind of bird they were Was the best kind of bird And they deserved it? What if the birds Thought that the earth and moon and stars Had been created just for them To do with as they pleased, To be their garden, their playground, their battlefield, To be the stage on which their mighty deeds were enacted And their glorious dreams Erupted into reality, And what if they thought the creator of the universe Had feathers and a beak, And what if the separate flocks of birds Each had their own bird-god they worshiped And each believed that their bird-god was the only true one And they hated the worshipers of the false bird-gods And slew them and enslaved them By the thousands and the millions? And what if the birds were far more powerful Than any other creature on the earth, And they spread all across the earth On relentless, unstoppable wings, And their numbers grew and grew, Doubled and doubled, Tripled and tripled, Because no other creature could stop them, And what if they saw No limits upon themselves, They could do whatever came into their heads, They could pile up glittering mountains of riches, They could vanquish illness, They could live forever, And many of the birds quit believing in their bird-gods Because they thought that THEY were becoming gods, And what if the other creatures were dying By the millions and the billions But the birds didn't care Because the earth belonged to them? And despite all their power, What if the birds were not happy, And continued to fight furiously among themselves, To ravage each other with their savage, bloody beaks, And what if they could never forget They were going to die, Just like all the other creatures of the earth They would turn into dust and ash And vanish forever from the earth, And they were sick with the fear of dying, And some of them began to realize The earth itself was dying, Its water and air poisoned, its forests burning up, And though their wings were strong There was no other planet they could fly to, And what if in their madness they could still not stop themselves From ripping at the earth in a final frenzy To extract its treasures, to achieve more power, and to become The richest and the greatest bird of all? But the birds are not like us. They warm themselves in the sunlight, Fluff up their feathers against the cold and rain. They find food, and make love, and never think of death, And fly from place to place like gods. In the morning they wake up And at night they go to sleep, Unless they're owls And spend each night under the magic moon.

2 Comments

|

Tom Epperson is a novelist and screenwriter who lives in Los Angeles. Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed